The difference between a tantrum and a meltdown

They are not intentionally trying to embarrass you...

Have you ever seen a child in the supermarket crying, screaming and perhaps even lying on the floor while their helpless care giver looks distressed?

Or maybe it was your child acting this way while you felt all embarrassed?

I remember picking up my daughter from the supermarket floor while she was screaming when she was about 2 years old. And all because I told her that she couldn’t take all the flowers home from the exit as we were leaving. I rolled my eyes, picked her up and put her under my arm like a football as I left the supermarket as quickly as I could. But not before getting a few disapproving looks from people who have most likely never had kids or don’t remember what kids are like.

Tantrums and Meltdowns can look very similar as the child may show the same behavioural responses for either including: screaming, crying, hitting, kicking and/or throwing. However tantrums and meltdowns are actually very different, and the way to support children through these emotions is also very different.

WHAT ARE THE CHARACTERISTICS OF A TANTRUM?

Tantrums are driven by a want

What my daughter was experiencing in the supermarket was undeniably a tantrum. She saw something that she wanted, and she was letting me know that she wasn’t happy that I wasn’t giving into her want. Toddlers and young children are learning about themselves as individuals, and this age comes with a sense of entitlement. Therefore, they can’t understand why they would not be able to have what they want.

Tantrums are a normal part of development

Tantrums are very common with toddlers and in young children and are a normal part of development as the brain develops. During this time, children experience big emotions that they have not yet developed the physiological ability to manage. They are also starting to develop some understanding of the world, but vital areas of the brain for problem solving, reasoning and negotiation have not yet developed.

Tantrums are a method of communication

Young children’s expressive and receptive communication take time to develop and therefore they often don’t have the communication skills to verbalise what they are thinking, feeling or wanting. Therefore, tantrums are often a way that children express their frustration about not getting their opinions or wants understood by other people. This, combined with their inability to manage their anger and frustrations, can escalate the frequency and intensity of their tantrum.

Tantrums are usually conducted in front of an audience

As tantrums are a method of communication, they are generally conducted around the person who has told them “no”. If the person leaves the area, the child will either follow them to continue their tantrum in front of them, or if there is no one else around, they will end their tantrum.

Tantrums will end if they receive their want or the situation is resolved

As tantrums are driven by a want, if they receive what they originally wanted, the tantrum will end. This is because children have control over their tantrum. They have a tantrum as a form of communication or protest to express their anger or frustration that they can’t have or get what they want. Therefore, once they have what they want, the tantrum no longer serves its purpose and the child can end the tantrum.

This can be tricky for parents to manage, as parents know that if they give in to the cause of the tantrum, the child will stop their screaming, crying, kicking or throwing. However, if parents do provide the child with what they want, the child soon learns that if they have a tantrum, they will eventually get what they want.

Tantrums generally last under 15 minutes

Tantrums don’t last as long as meltdowns. A child will generally realise that they are not going to get their want by about 15 minutes, and they will move onto another activity.

WHAT ARE THE CHARACTERISTICS OF A MELTDOWN?

Meltdowns are driven by either over-stimulation through sensory overload or an increase in anxiety

Different from tantrums that are an expression of anger and frustration, a meltdown occurs following a situation that is extremely overwhelming.

Meltdowns can happen at any age and are more common with people with sensory processing difficulties. They may have an over-responsive sensory system. This can easily be overwhelmed through stimulus that people without the same sensory processing difficulties can manage and not even pay any attention to. An example of this is if someone is sensitive to noise and they enter a noisy room. This person may not be able to cope with the additional noise and their sensory system may become overloaded. The behavioural response to this over-stimulation may be screaming, crying, hitting, kicking and/or throwing which is the same behavioural response as a tantrum, however the cause of the behaviour is different.

Likewise, if a person is experiencing heightened anxiety, their nervous system is often more sensitive so the addition of sensory stimuli may also cause an over-stimulation and a meltdown to occur.

Meltdowns are an involuntary response

Meltdowns are beyond a person’s control and the person may be embarrassed either during or after the meltdown, but not have the ability to stop it if they want to. This is because a meltdown is activated by the fight or flight response in the brainstem and not controlled by the thinking parts of the brain. Originally the fight or flight response was developed as a protective mechanism to help us survive during times such as when predators were chasing human being into caves. Now the response is still activated when our bodies feel threatened, such as with stimulus that the body cannot cope with.

Meltdowns often end if there is a change in sensory input or when the person wears themselves out

Sometimes the meltdown will end when the overwhelming stimuli is removed or if the person is removed from the overwhelming stimuli. Using the example of the person with auditory sensitivities walking into a noisy room. The meltdown may end if the room went really quiet, noisy people left the room, or if the person was removed from the noisy room.

Meltdowns can use up a lot of energy and therefore they will often end when the person is exhausted from the behavioural response to the overwhelming stimuli. This could include being very tired or even falling asleep.

Meltdowns are slow to end and the person may require assistance and strategies

Even if the stimulus that has triggered the meltdown has been removed, or if the person has been removed from where the trigger took place, it does not mean that the meltdown will immediately end. Sometimes meltdowns take hold so strongly that simply removing the stimuli is not enough to calm the heightened nervous system once the sensory system is overwhelmed, and the nervous system needs additional time to readjust.

Sometimes a person needs assistance to end their meltdown by providing them with tools to help them calm down. These tools are generally tools that have a calming effect on the sensory system. However, it can be difficult to know when to intervene when a person is having a meltdown. If you intervene too early, it may cause the meltdown to escalate.

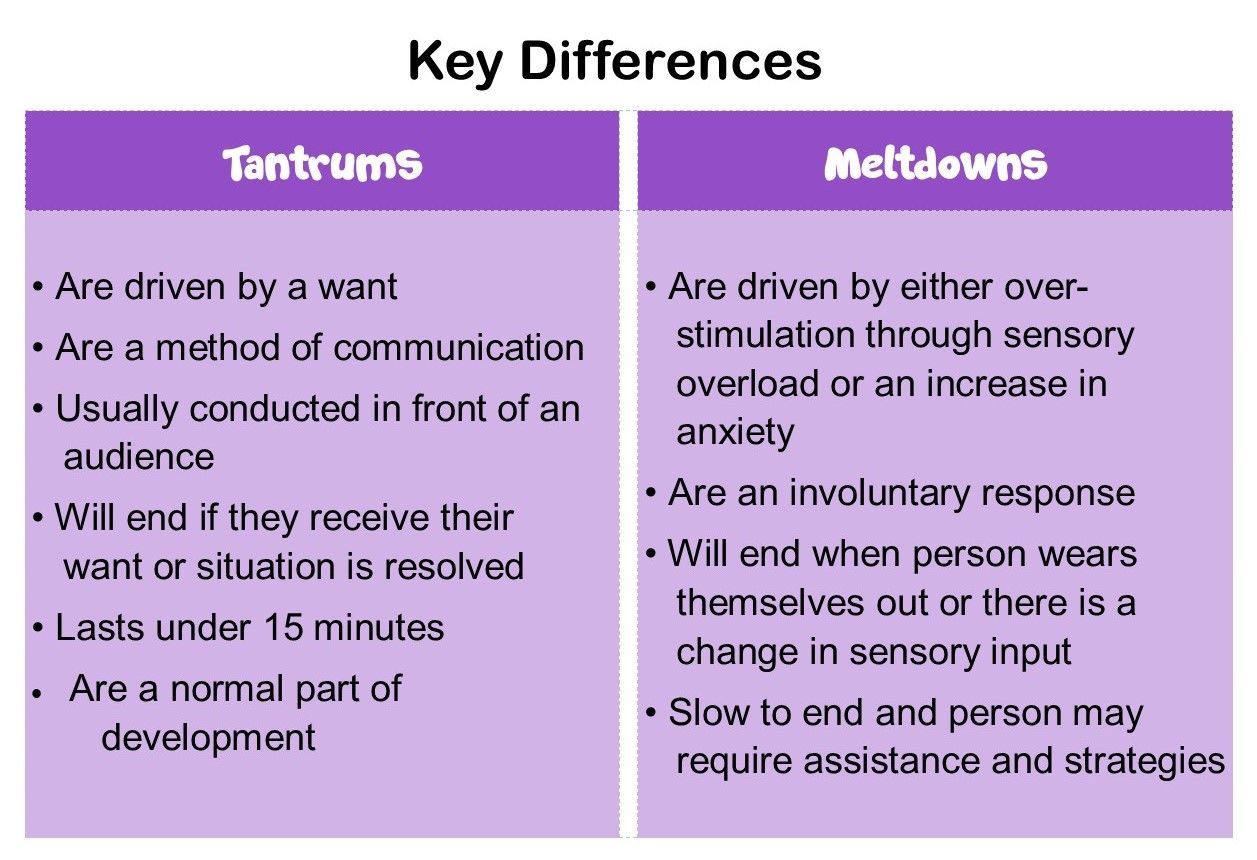

SO WHAT ARE THE BIGGEST DIFFERENCES BETWEEN A TANTRUM AND A MELTDOWN?

The key differences lie in the triggers and the control. While the tantrum is driven by anger and frustration from an unmet (and often unreasonable) request, a meltdown is triggered by distress due to sensory or emotional overwhelm.

Tantrums and meltdowns also use different parts of the brain. Tantrums use the thinking and feeling part of our brain. The child maintains control and can pause the tantrum if they choose. However as discussed, meltdowns use the fight or flight part of our brain and the child cannot control the meltdown.

Tantrums in older children are generally due to a learned response where they know that if they continue their tantrum, they will eventually get provided with what they want. It can become a learnt strategy to maintain control.

However, it is possible for a child to commence a tantrum that turns into a meltdown if they become very heightened during the tantrum. The child may start to lose control of their tantrum and no longer have the ability to stop when they want to.

HOW TO SUPPORT A CHILD THROUGH A TANTRUM

In research, there are many different approaches to supporting a child with a tantrum, therefore I have chosen to describe the common themes and approaches.

Ignore the unwanted behavior, focus on the desired behaviour

We know that a tantrum is driven by a want and the young child does not have the cognitive skills to process why they cannot have what they want or negotiate a more acceptable outcome. It is therefore worthless saying things like, “calm down” during their tantrum. This may just make the child more frustrated or angry, thus intensifying the unwanted behaviours associated with the tantrum.

Instead of trying to control or change the behaviour, we should ignore the behaviour that is associated with the tantrum. We want to reinforce which behaviour is most appropriate in the situation. Choose a phrase where the child can clearly understand what is expected of them in the situation, and repeat the phrase to enforce the desired behaviour. This could look like, “You will get your turn to play, after you wait your turn”. Repeat phrase as required.

Reinforce the desired behaviour

If there is another child around, comment on the other child’s good behaviour to help the tantruming child understand the desired way to act in the situation. You may say something like, “Thank you for waiting your turn so quietly. I’m so proud of you for listening.”

Acknowledge when the child is changing their behaviour

When the child’s tantrum is starting to ease, it is a good idea to acknowledge that you notice and appreciate that their behaviour is changing. This reinforces that you are not paying attention to them when they are having a tantrum, but if they change their behaviour, they will receive some attention. An example of acknowledging and praising them for changing their behaviour could be, “Thank you for calming down. I am so proud of you for working hard to control your feelings.”

Avoid negotiating during the tantrum

We know that a young child does not have the cognitive ability to understand why they are being unreasonable with their request. They are so focused on what they want and should be entitled to, that trying to negotiate with them is not going to be effective. For slightly older children, if you offer something related to what they are trying to obtain during their tantrum, they may still feel like they are getting their own way. Therefore, they could learn that if they have a tantrum, they get something similar to what they want. This could lead to a learned behaviour of more frequent tantrums.

Instead, teach the child that they can negotiate when they are calm. For example, “I would be happy to talk about other choices when you are calm and ready.”

Reinforce connection

A young child having a tantrum is not a “naughty” child. It is important to recognize and remind yourself that tantrums are a developmental norm that will change when they have learnt the skills to communicate, understand another’s point of view and negotiate effectively. We do not want the child to be treated like they are being “naughty”, as this can impact their self-esteem and the connection between the child and the adult. An effective way of maintaining a connection while ignoring the undesired behaviour is saying something like, “I see that you have some big emotions at the moment. Let me know when you are ready for a hug”.

With my own experience, I would not intervene or negotiate with the child having a tantrum, but I acknowledged that I was there for them when they were done. I noticed that every time I offered a hug once their tantrum was over, they would eventually come over and give me a hug. As my children developed more understanding, I took this opportunity to explain my decision regarding why they couldn’t have what they wanted. They often even apologized for their behaviour and then we would continue on with our day. This gave me an opportunity to help them with their emotional development.

HOW TO SUPPORT A CHILD THROUGH A MELTDOWN

The most effective way to support a child who has meltdowns is to understand what causes their meltdowns and try to avoid situations that are likely to be a trigger. Here are some strategies to reduce meltdowns.

Prior To A Meltdown

1. Plan ahead

Ensure you have a good understanding about the child’s sensory preferences.

As we spoke about earlier, everyone’s sensory system processes information differently and some people with sensory processing difficulties can easily become overwhelmed when there is too much of a particular stimulus. These can include things like being sensitive to noise, lights, touch, temperature or movement. By knowing the child’s sensory preferences and how they respond to different stimuli, we can be more prepared when we need to attend a place that may involve a lot of overwhelming sensory information for the child.

Know what tools help to calm the child down, and have these on hand.

Strategies to calm or prepare the nervous system for an increase in sensory stimuli are different for each person. If we have an understanding of what tools we can put in place to reduce the chance of an overstimulated sensory system, it can help the child cope with the situation at hand and may prevent or lessen the intensity of a meltdown. An example of this is if a person is sensitive to noise, but you need to take them to a busy shopping centre. You could offer headphones to reduce or block out the noise so that the person can cope with the environment much easier. Other strategies that may work for some people could include wearing tight clothing, holding a special toy, nibbling on a favourite snack or being provided with a big hug. If you want assistance to determine which tools or strategies to use in different situations, you can speak with an occupational therapist.

Prepare the child for what is going to happen

Some people thrive on predictability and unexpected or uncertain situations can increase anxiety. As anxiety can heighten our nervous system, some people can handle less sensory input if they are anxious. Therefore, if they understand what is going to happen, it can alleviate some anxiety and help the child cope better with the situation. A simple way to do this is having a structured routine for common activities or a social story to for new activities.

2. Intervene

Look for signs that a meltdown might be brewing

Children often show signs that they are struggling prior to their meltdown. Look for signs such as restlessness, fidgeting, worried facial expressions etc. When noticed, remove the child from the situation or provide them with their sensory tools to help calm them down before their meltdown begins. If the uncomfortable stimuli can be removed or if they can remove themselves from the environment prior to the meltdown starting, it may stop the meltdown from eventuating.

During A Meltdown

A meltdown can be distressing for both the child and for the adult. Once a meltdown has commenced, it is important to remember that the child cannot be reasoned with, as they are not in control of their behaviour. Try these strategies when a meltdown occurs.

Take a big breath

It is important to keep yourself calm so that you do not also enter the ‘fight or flight’ response. A dysregulated adult is not able to support a dysregulated child, and may escalate the child’s reaction further.

Ensure the environment is safe

When a meltdown is in full swing it is important to remove objects in the environment that can be harmful for the child or adult. This could include removing items that the child could throw or ensuring there are no objects that they could throw themselves onto.

Minimise input

Talking to the child at the height of their meltdown could actually escalate them further. Although, sometimes the occasional verbal reassurance can be useful, depending on the child.

Following A Meltdown

Comfort the child

Meltdowns can be emotionally and physically exhausting. As the meltdown starts to reduce, the child may be ready to accept words of reassurance and comfort.

Offer the child choices

Offer the child options to help them continue to calm down. This may be their sensory tools, a hug, a walk, or anything else that you determine is appropriate for the situation that is low stimulation.

TAKE HOME MESSAGES

- Even through tantrums and meltdowns can look the same, they are different and the way we support children through each of these is different.

- The main differences between a tantrum and a meltdown are where the control lies and what the triggers are.

- Tantrums are a communication strategy to express the child’s protest with something and the child remains in control of their behaviour.

- It is important not to give in to tantrums as it can become a learnt response. Instead, ignore the unwanted behaviour and focus on the desired behaviour.

- Meltdowns occur as a state of extreme overwhelm and the child is unable to control their actions during the meltdown.

- Meltdowns can be reduced by knowing the child’s sensory differences or preferences and planning ahead.

- During a meltdown, a child may require assistance to help them calm down, but the timing of the assistance varies and can escalate or reduce the meltdown.

If you would like a free summary of the main differences between a tantrum and meltdown and the ways to support a child through both of these, please click here: